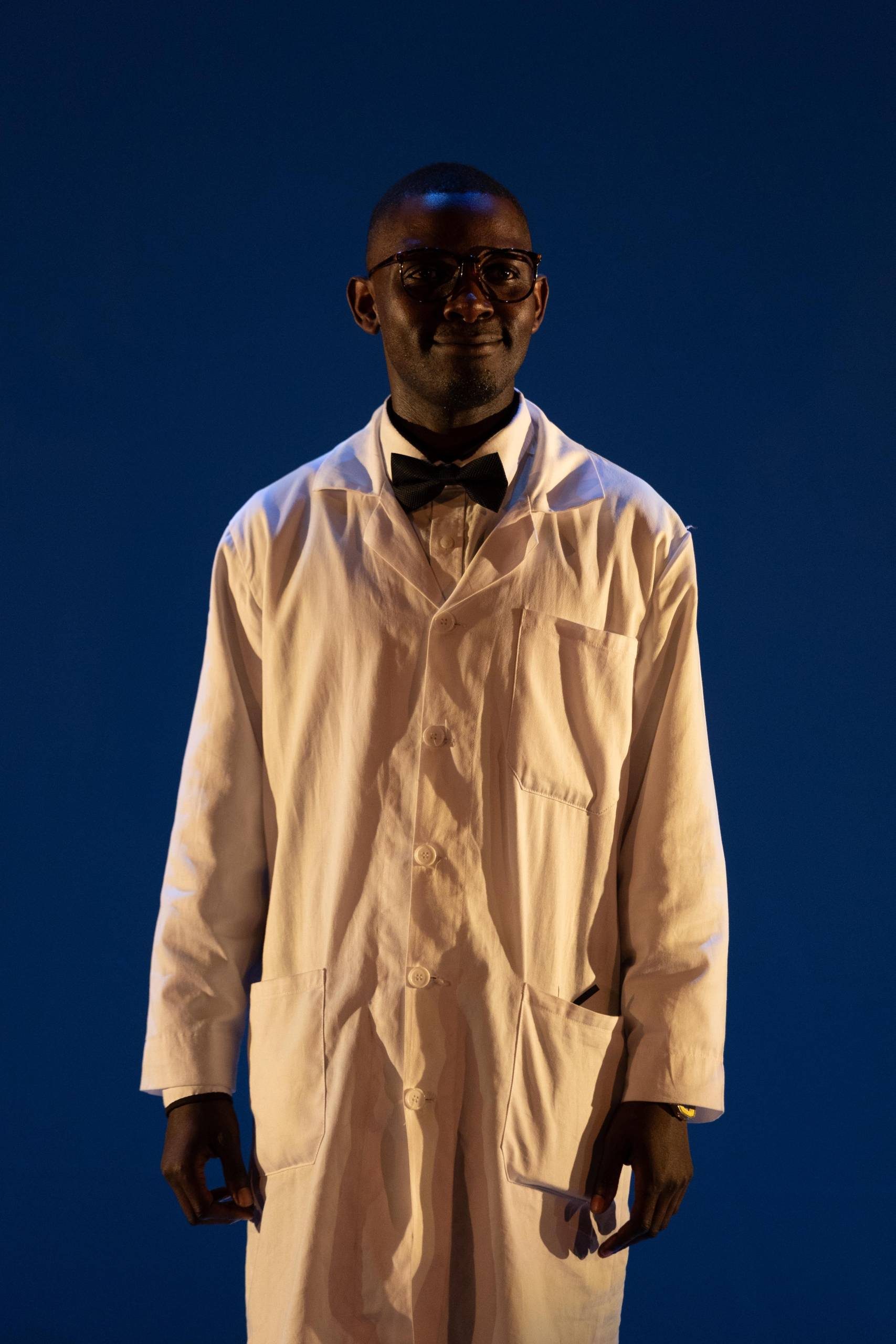

We spoke to John Pfumojena, the director of Sizwe Banzi is Dead, to find out more about the show.

What is Sizwe Banzi is Dead about?

Sizwe Banzi is Dead is a play written by Athol Fugard in collaboration with John Kani and Winston Ntshona. The play is about Styles, an intelligent, capable, and talented man who leaves his job as a factory worker to follow his dream of owning a photography studio. Styles pursues his talent with a camera in order to preserve the faces and identities of his people, who would otherwise be forgotten by the rest of the world. The play also features an African man (Sizwe Banzi) who leaves his home to try to find work in another city but is unsuccessful and is told that he has 3 days to vacate the town. He stays with a friend named Buntu, and the both of them find a dead body in the alleyway.

Who is this play for?

Created and first performed in Cape Town, 1972, this a significant piece of work in South African theatre, dealing with the issue of identity in the apartheid era. This era was a period of institutionalised racial segregation which ensured that South Africa was dominated by white citizens who had the highest status. The style and themes of this play ensure an unmistakable relevance to a breadth of audience members.

Young and elderly patrons can enjoy the presentation of this African Township Theatre style not common or prevalent on British stages. It’s a very witty and playful 2 hander show considering the context of the drama.

It would appeal to theatre patrons who enjoy thought-provoking, historical, and politically aware works. Given its historical context and poignant themes, it would also attract those interested in South African history or apartheid.

This play could be useful for schools, universities, and other educational institutions, particularly for those studying drama, African studies, or history.

It might also resonate with activists and people interested in social justice, as the play focuses on racial identity and the struggle for human rights.

Although “Sizwe Banzi is Dead” is rooted in a specific historical and cultural context, its themes of identity, freedom, and resistance have universal relevance.

What was it that drew you to this play?

Although I have been involved with performance, music and storytelling from the early age of 6, Sizwe Banzi is Dead became the best play I had read circa 2004/5. The play text was a set book for our Literature in English studies in high school when I was at Prince Edward School in Zimbabwe. Aside from understanding the apartheid context of the story, this play read easily and proved quotable with the memorable lines and witty existence of the characters. I read this play almost everyday for the 2 years of study in high school, and probably gave it more attention than the other texts, admittedly. It is then that I vowed to stage this play at some point. The themes in this play are so relevant today as we navigate immigration, refugees, visas, racism in a world that is supposed to have advanced post colonially. So in a manner of speaking, Sizwe Banzi is ALIVE today. It is important to me as a Southern African creative to expose more sub-saharan theatre styles and classic stage plays to the wider UK audience.

The play in originally set in 1970s apartheid South Africa. What parallels do you think can be taken from modern day life? Is this reflected in your version of Sizwe Banzi is Dead?

The play explores themes of identity, family, freedom, dignity, racism and survival under oppression, just to mention some. I think some parallels can be drawn from modern day life, such as the ongoing struggle for racial equality and justice, the impact of migration and displacement on people’s lives, and the power of storytelling and memory to resist oppression and erasure. I think these issues are still relevant and resonant today, especially in light of recent events such as the Black Lives Matter movement, the refugee crisis, and the rise of authoritarianism and nationalism in some parts of the world.

In my version of Sizwe Banzi Is Dead, I would try to reflect these parallels by using contemporary costumes, music and props to create a connection with the audience. I would also try to highlight the humour, resilience and humanity of the characters, as well as their pain and suffering. I would hope that my version would inspire the audience to think critically about the past and the present, and to empathize with the experiences of others who are different from them.

As the Director, what are the most important elements in your process to bring the show to life?

As a Director, co-creation and collaboration is important as this highlights an integral part of Bantu and Southern African culture where traditionally there was never a word for theatre because we lived our theatre through rituals, cultural ceremonies, celebrations and so on. The intricate convergence of full production elements to focus on the storytelling is important even before the rehearsal room is animated. Ownership of the story from all creative and technical team and cast is an invaluable element of my process and this reflects oral traditions synonymous with Southern Africa. Everyone is telling their part of the story as dramatically as sitting round a fire in the village and listening to one’s grandmother narrate intricate adventures. An extensive knowledge of the world then coupled with knowledge of the world now and the parallels, provide a depth to character approach. Above all, improvisation in the room allows the players to shed a seemingly restrictive text and just tell the story in first person with emotional and relative experiential understanding.

Are there any challenges in achieving this?

The British weather. (I wish I was joking). (laughs). The very process of creating theatre for consumption by audiences is a challenge and that is what makes the ordeal all the more exciting. Every play one witnesses on stage is a result of overcoming multiple unsung challenges. Rather, I focus on telling the story how we want to tell it.

Can you tell us more about the character of Styles? Who is he and what is his relationship to Sizwe?

Styles sets the scene and background of the world in which the play takes place, and he is a proud self-employed Photographer in the heart of New Brighton, with a swanky photo studio dedicated to documenting all the black people and fulfilling their dreams with pictures. He knows what it’s like to work under an oppressive system, having worked at ford factories under a white boss until he freed himself and started his photography business. He views every black person who walks into his studio as ‘a dream’ waiting to be fulfilled through his lens. Styles addresses the audience in an oral tradition style that is deliberately telling the audience anecdotes and witty stories of what he has experienced and what has occurred in the land. Up to the point where there is a knock on the door and a man walks in to have his picture taken. This is Sizwe Banzi. Styles shoots a photograph of Sizwe Banzi that launches the adventure of the play into action. For Styles, Sizwe is just one of the many black people he has photographed, but for Sizwe this photograph is his first!

Why should people come to see this play?

Watching this play is a great introduction to classic Southern African Theatre which also doubles as a little history of the time and region. The text is important now more than ever as it could have been written today in light of the socio-political landscape of the world that’s rooted in the suppression of black people and immigrants. It is when you watch this play that you realise how repetitive history is but how simple the needs of each human individual are. Regardless of backgrounds, we can all relate to themes of identity and even something as simple as losing your name. Each character in this play does not represent an individual but, as I say, ‘it represents a people in a situation’. ‘Sizwe’ means NATION, now that should help audiences better understand the play regardless of its setting and situation especially in relation to the state of our modern world.

Do you have any advice for people looking to get into the theatre industry?

Everyone has a story or stories to tell. So tell them.

You can see Sizwe Banzi is Dead here at Mayflower Studios on 6 -14 October 2023.